One of the main drivers behind Australia’s year-to-year rainfall and temperature variability is approaching record strength, second only to the peaks of 2019.

While El Niño in the Pacific dominates the headlines due to its global influence, the Indian Ocean actually has a greater impact on Australia’s weather during spring, and a pronounced shift in water temperatures to our west is already spreading drought and frequent spells of hot weather across the country.

South Australia was sizzling on Wednesday, as maximums soared up to 14 degrees Celsius above average for October, while Victoria climbed as much 13 above normal.

Adelaide’s high nudged above 32C, the city’s hottest October day in four years.

This week’s heat is the result of a north-westerly blowing south from the tropics, however the summery weather will remain short-lived as a cooler south-westerly change arrived promptly along the southern coastline on Wednesday evening.

While Adelaide and Melbourne were shivering through a much colder Thursday, the hot north-westerly spread east across NSW.

Sydney climbed above 30C for the seventh time this spring on Thursday, well above the average to this point in the season of just one day above that mark.

A cool change from the south-west will lower NSW temperatures by Friday, but hot weather will spread to south-east Queensland and push Brisbane above 30C.

How does the Indian Ocean change Australia’s weather?

Most years have a neutral Indian Ocean, where water temperatures are near normal, but in about one third of years, large pools of opposing warm and cold water develop on either side of the tropical Indian basin during winter and spring.

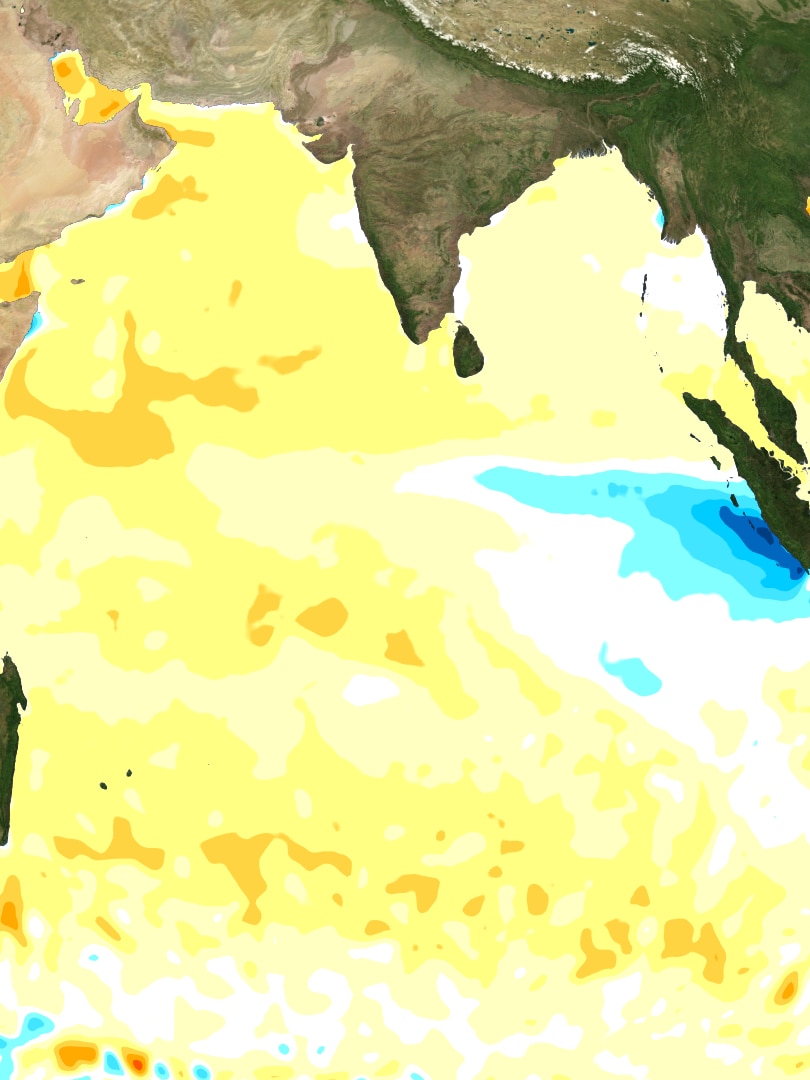

The phase which developed this year is called a positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), and is marked by cold water near Indonesia and warm water off the Horn of Africa as shown in the map below.

Since warm air expands and cool air contracts, cold water promotes high pressure systems and warm water promotes low pressure systems.

Because winds blow from high to low pressure the changes in ocean temperature therefore alters the direction of the wind blowing along the equator between Africa and Australia.

In a normal year the wind blows from the west to the east, which helps cloud and rain to develop over our longitudes, however during a positive IOD the wind direction is reversed, blowing to the west.

As winds blowing to the west are moving away from Australia, this leads to below average rain across the vast majority of our country, well beyond the scope of El Niño which mostly impacts just the eastern states.

The lack of cloud, and subsequent increase in sunshine then leads to warmer daytime temperatures, including a higher frequency of extreme hot days and prolonged heatwaves.

This warming and drying impact was already well established through September which was Australia’s driest on record and third warmest.

How the IOD will impact the rest of 2023

This year’s positive IOD pattern formed in August, strengthened rapidly through September, and is now challenging previous years for intensity, including the record strong 2019 event, which laid the platform for the Black Summer bushfires.

The latest weekly index value used to measure the IOD is +1.85, more than four times the positive threshold of +0.4, and second only to the peaks of the 2019 event which briefly passed the +2 barrier for three weeks.

So does that mean the rest of 2023 will rival the horror finish to 2019?

Even excluding the fact 2019 was preceded by the worst multi-year drought on record, thankfully the answer is still no.

That’s due to rare event in spring 2019 called a Sudden Stratospheric Warming when the polar vortex over Antarctica weakened.

This relaxing of the vortex allowed westerly winds to escape north from Antarctica towards Australia, sending hot, dry desert air from the interior towards eastern Australia.

While hot, dry and windy weather is still likely from October to December this year it’s unlikely to occur as frequently as seen four years ago.

The other positive to an otherwise grim spring forecast is IODs rapidly decay in December when the monsoon arrives in the Southern Hemisphere.

This seasonal burst of north-westerly winds will replace the easterlies currently blowing away from Australia, and as a result increase the chance of rain.

This more optimistic appraisal of rain by summer is already reflected the Bureau’s official three-month outlooks, which now shows a near even chance of wetter or drier conditions through summer for much of the country.

Posted , updated