“Get up, stand up, don’t give up the fight.”

Bob Marley’s lyrics unexpectedly bounced around South Australia’s upper house late on Tuesday night.

Legislative councillor Frank Pangallo recalled the time he chauffeured the reggae artist around Adelaide, reading the Jamaican’s words into the public record during a more than five-hour speech opposing a bill he called a “faecal sandwich”.

It may have been a colourful way to describe the state government’s changes to the Summary Offences Act, but it’s been a sentiment that’s been shared by the broad coalition lining up to oppose the bill.

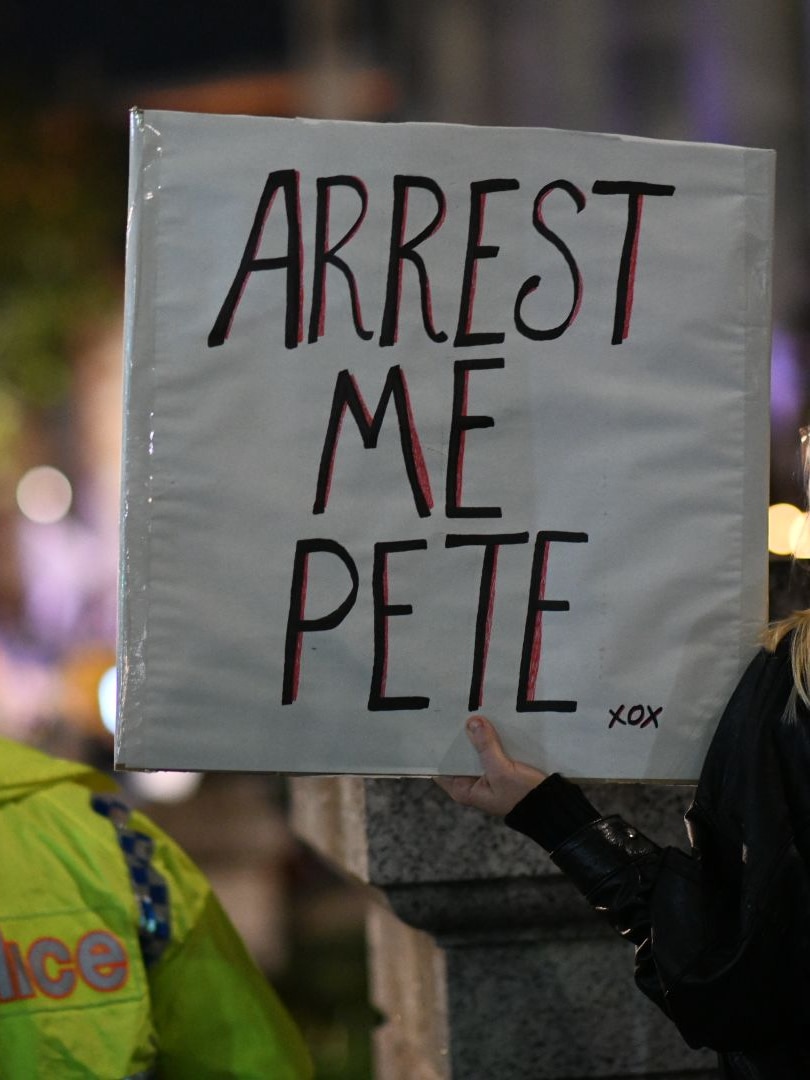

That opposition sparked sizeable public protests and unrest stretching from some inside the Labor party to key union backers, but it was not enough to stop the contentious legislation.

After more than 14 hours of overnight debate, mainly due to the filibustering efforts of the upper house crossbench MPs and the unwillingness of the major parties to adjourn, the reforms passed just before 7am on Wednesday with three minor amendments.

It means the maximum fine for obstructing a public place jumps to $50,000 and three months jail.

The government — and opposition for that matter — say it will give the courts the discretion to impose harsher penalties than they could under the existing regime.

The trigger for the changes was two days of disruption on Adelaide’s streets earlier this month by climate change protesters amid an oil and gas industry conference.

They were floated by the Liberal opposition, quickly adopted by the government with minimal internal or external consultation and shunted through the lower house of parliament in less than half an hour with bi-partisan support.

Between debate in the two houses, there was backlash from human rights groups, the Law Society of South Australia and the union movement, which helped get Labor elected in 2022.

The state government has argued the changes are not anti-protest laws.

When he spoke in parliament on May 18 as the changes were introduced, Premier Peter Malinauskas said the government considered protest and speaking up as “an integral part of our vibrant democracy”.

“The government does not seek to prevent members of the community from having their say,” he told the house.

Earlier in the speech, he said:

“Irrespective of the causes that protests are aimed at, the way that the protests are increasingly conducted puts the safety of the public at risk.”

A press release issued by the premier’s office shortly after the rapid passage of the bill in the House of Assembly was titled “Tough new penalties for dangerous and obstructionist protesters”.

“We have swiftly introduced legislation that increases the penalties for those who do not seek to comply with appropriate arrangements when it comes to protesting peacefully,” he told reporters at the time.

Mr Malinauskas has repeatedly pointed out it’s the Public Assemblies Act that governs organised protests, a piece of legislation itself that makes no mention of the word protest or protesters.

“There is nothing changing to that. Not one word. Not one comma. Not one full stop,” he said.

Others have seen the impact of the Summary Offences Act changes on protesting in South Australia differently, including allies of the government.

“This bill fundamentally threatens our ability to take action like this, in the interests of our members and the South Australian community.”

They are the words of Leah Watkins, secretary of the Ambulance Employees Association, as she addressed a crowd on Tuesday morning rallying against the bill as Labor MPs met at parliament.

As a senior figure in the paramedics union, in recent years she has stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Peter Malinauskas and Labor MPs to push for better resourcing for the state’s ambulance service.

“The fact that we are facing these laws without any community consultation, without any engagement with the community whatsoever, is outrageous,” said the president of SA Unions Dale Beasley to the same rally.

He went on to add he was “really worried” about what these laws were going to mean for workers who take action in and outside their workplace.

“This is a very serious piece of legislation that deserves time and consideration and that’s not something that we’ve had,” he said.

Steph Key, a former Rann Labor government minister, told hundreds of people gathered on Festival Plaza there was “no excuse” for the way the legislation was handled.

“By ramming through that legislation, there’s no excuse for it, and I don’t support it at all,” she said.

“We really do need to make it clear that protesting is a right that we should have.”

The government’s decision to make its move so quickly could be seen to have some echoes of the Rann-era so-called “announce and defend” style of leadership — an approach his successor Jay Weatherill tried to distance himself from.

Or maybe the Malinauskas-led administration just wanted to move quickly so the issue didn’t drag on, nor give the opposition the upper hand.

When asked whether this was his government’s Land Tax moment — a reform that fired up regular Liberal Party supporters last term – Mr Malinauskas said that issue didn’t get resolved by the parliament for “almost a year” while Summary Offences reforms were sorted “relatively quickly”.

But, whatever the reason, tensions have been publicly inflamed with traditional friends of the Labor parliamentary party for the second time in little more than a year, following the back and forth over changes to the state’s Return to Work scheme.

After the bill passed, Mr Malinauskas said it wasn’t a question about people’s ability to protest.

“It’s a question of every other citizen in the state that wants to be able to move through the city safely and with confidence that it’s happened in an ordered way,” he said.

As things stand, though, the Malinauskas government’s relations with some key unions — the people who pay the bills at election time — have been hit.

It has left some on the left side of politics wondering whether that fight could and should have been avoided.

Posted , updated