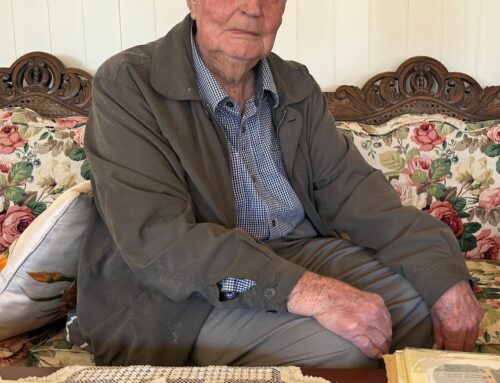

Steve Connelly describes it as a feeling of being “completely unplugged”.

In 2018, Steve and his wife Tamarah were playing a pre-dinner game of backgammon in their Mackay apartment.

According to Tamarah, Steve became very quiet, before closing his eyes and making “groaning sounds”.

He lost consciousness for about 10 seconds, before coming to.

“I thought I better have a lie down, which I did,” Steve Connelly says.

“But I didn’t get any better.”

While Steve was recovering, Tamarah called their regular GP — Jennie Wright — in their home town of Adelaide, who instructed her to call an ambulance.

While he lay in hospital under monitoring, Steve would have another 10 similar events before a cause was found.

Steve’s heart was stopping.

“They couldn’t work out why it was stopping, but it was stopping for about 10 seconds at a time,” he says.

“The doctors said, ‘Look, what you need — first off — is to keep the heart going. So you need a pacemaker. And then you need to find out what’s causing it to happen.'”

They also told him that the relevant surgeon in the area was away, so it would be best if they returned home to Adelaide for the life-saving operation.

“So in the space of a few days, I went from putting along nicely in Mackay, living a good life to all of a sudden being on a plane, not exactly sure what was going on,” he says.

“Jennie [our GP] organised the specialists and a pacemaker was inserted a couple of days later.”

Quantity: 5km, once a week, five repeats

With their lives turned upside down, Tamarah noticed a significant shift in Steve.

“He is normally very confident and outgoing, but he completely changed,” she says.

“And we were both very nervous about leaving each other because I was scared he was going to collapse.”

As Steve describes it, their world, once big, became “very small”.

Having suddenly quit his job as a technical writer in Mackay, and with their house rented out in Adelaide, Steve and Tamarah moved into a caravan park.

For six weeks after his operation, Steve was unable to lift anything heavier than 2 kilograms, or raise his arms above his head while the wires of his pacemaker set.

“My whole focus then became my health,” he says.

Tamarah says he became “very depressed”.

At this point, Steve returned to see Dr Wright at her Adelaide clinic.

As he relayed the changes in his mood, she began to type on her computer, before printing out a script.

“I thought, ‘oh, this is antidepressants or something similar — something I didn’t really want’,” Steve says.

What Dr Wright prescribed, however, was not medication: it was a script for “parkrun”.

Quantity: 5km, once a week, with five repeats.

“He was just expecting it to be a tablet,” Dr Wright recalls.

Australian GPs keen to increase ‘social prescriptions’

In writing Steve Connelly a script for parkrun, Dr Wright undertook what in the UK and elsewhere is commonly known as “social prescribing”.

At its simplest, social prescribing refers to the practice of referring patients to local, “non-medical” activities or services.

Examples might include suggesting a patient join a group activity like tai chi or meditation classes.

In a recent survey of almost 3,000 Australian GPs, 69 per cent said they were already “prescribing” parkrun to their patients, while 87 per cent said they would consider doing so in the future.

In Dr Wright’s case, the choice to prescribe Steve parkrun was an evidence-based decision rooted in personal experience.

Now a veteran of no less than 250 parkruns, Dr Wright started going to parkrun during a difficult patch of her own, initially, she says, as a form of “stress relief”.

“I started running on the treadmill, but I was too self-conscious [to go outside] thinking people would be critical,” Dr Wright says.

When her brother told her about parkrun, she reluctantly agreed to go, assuming she would hate it.

“I thought all these athletic people would be very scathing on someone like me,” she says.

“But it wasn’t like that at all. It was a very welcoming environment.”

After giving Steve his “prescription”, she offered to join him and Tamarah on their first parkrun.

“It made us feel safe, knowing Dr Jennie was there,” Tamarah says.

“We also knew there were defibrillators at the event, so there was help there if we needed it.”

From depression to 21km: Steve’s transformation

It turned out to be a fateful choice; 61 parkruns later, Steve has come a long way from Mackay.

While at first he walked the 5km parkrun course — which is a choice open to all participants — he eventually built up to running.

To his own disbelief, in October 2021, Steve would go on to compete in a half-marathon, cheered on by a group of friends and, of course, Tamarah.

“I was in tears, just picturing where he was back in Mackay,” Tamarah says.

“And then thinking about him at Dr Jennie’s, being so depressed. The progression to doing parkrun and being able to walk, then run and then do 21 kilometres was just unbelievable.

Steve says crossing the 21km half marathon line also gave him pause to reflect on his journey.

“I thought, ‘how in the world did I do this?'” he says.

“Considering where I was before; I wasn’t even walking. I’d take the car everywhere.

“Now the future is much bigger. All these doors have been opened which I definitely thought were closed. I’ve got choices; we can do things I never thought were possible before.”

‘Parkrun practice’ initiative follows UK success story

Today, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) will announce a formal partnership with parkrun, encouraging more GPs to refer their patients to parkrun by signing up as official ‘parkrun practices’.

A similar initiative was rolled out in the UK in 2018, which has seen 74 per cent of all GP practices refer patients to parkrun.

According to RACGP president and adjunct professor Karen Price, the parkrun partnership is particularly attractive because of its capacity to address high rates of chronic disease in the community.

“Up to 49 per cent of chronic diseases have a basis in modifiable risk factors,” Dr Price says.

“Social prescribing is an opportunity to embed patients in community activities that can address some of those risk factors.

“People with chronic illness don’t just suffer from diabetes, for example, they often have a component of mental [ill] health that goes with that.

In this context, she says, community activity is as much about social connection as it is physical activity.

“Community activity gets people up and going,” she says.

“With parkrun, you can do 5km on a Saturday morning, it’s free, you can walk, you can run, you can crawl, you can spectate, you can be one of the volunteers.

“That contributes a lot because obviously the exercise is good, but so is mingling and feeling a sense of belonging in the community.”

‘It makes you feel like you’re part of something bigger’

Diane Sinclair, another one of Dr Wright’s patients, can attest to this.

Like Dr Wright, she started parkrun in a bid to relieve stress, but was also seeking a non-pharamaceutical solution to blood pressure problems.

She has now participated in more than 100 parkruns, and goes as far as planning her holidays around parkrun locations.

While each parkrun course might be different, she says, the sense of community is permeable.

“Last year, we had five deaths in the family in five months,” she says.

“My niece had pancreatic cancer, and we knew she wasn’t going to last. The people at parkrun knew what was going on and they were really supportive.

“They all understood why I was just mesmerised by this rainbow.”

Last year, a group from her local parkrun also joined her family on a charity run to raise money for cancer research.

“We’re a very tight-knit group of people. We always get together at the end or beginning of a parkrun and have a chat or go for a coffee, it’s really nice.

“It makes you feel like you’re part of something bigger.”

Glen Parker, parkrun’s head of health and wellbeing, says his hope is that the RACGP partnership gives more people like Steve and Diane access to the health and wellbeing benefits this sense of community brings.

“Coming out of pandemic restrictions, 71 per cent of our participants surveyed said the reason they came back to parkrun was to feel part of that community.

“When you ask people who they trust the most, it’s GPs first and daylight second — and they’re having conversations with people who have a lot to gain from those peripheral benefits of parkrun.”