The traditional Latin mass is a form of worship that can be mystical and beautiful, but it’s also at the centre of a division within the Catholic Church — between those who hanker for powerful priests and a more rigid church, and those who embrace greater involvement of the congregation.

Key points:

- Pope Francis has restricted the use of the traditional Latin mass, shocking traditionalists

- Australian archbishops are responding to the changes, with some saying they will allow Latin mass to continue while they further consider the changes

- The Latin mass is a symbol of an older style of Catholicism, and has become a source of division between mainstream and traditionalist Catholics

Angela McCarthy, an adjunct senior lecturer in theology at the University of Notre Dame Australia, said she was brought up with Latin mass before the switch to what is known as the “ordinary form”.

“I remember really clearly, but I also remember not being able to respond,” Dr McCarthy said.

A priest saying the Latin mass speaks in Latin and has his back to the people.

Supplied

)The Latin mass, or Tridentine Rite, was the norm for 400 years.

Its last update was made in 1962, and it was replaced in the 1970s, following the Second Vatican Council, with the ordinary form of the mass.

The new form made it “much more clear that it’s the people of God who are engaged in this” and there was overwhelming support from bishops all around the world for the change, Dr McCarthy said.

She said it was a significant but positive change in her view.

“[Latin mass] was something that was, yes, mystical and beautiful but when the Latin mass disappeared and … we were able to say it in our own language, I became much more energised by that experience and [it] changed my experience of church.”

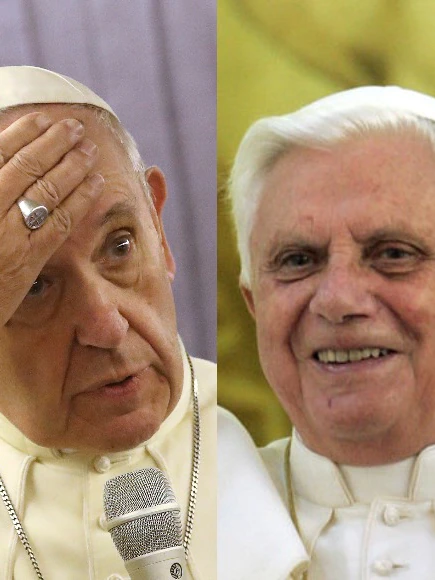

Pope Benedict brought it back but then a new pope had a different view

AFP: Osservatore Romano

)Some Catholics, however, continued to call for the return of the traditional Latin mass, and, in 2007, Pope Benedict XVI lifted restrictions on its use.

His successor, the more progressive Pope Francis, shocked Latin mass communities when he recently reinstated restrictions on its use.

In a letter to the world’s bishops, Pope Francis said he was “saddened that the instrumental use of the [1962 version of the Latin mass] is often characterised by a rejection not only of the liturgical reform, but of the Vatican Council II itself”.

Priests who have been celebrating the Latin mass now need permission from their bishop to continue to do so, and those who become priests after the Pope’s instruction was published must apply to their bishop, who in turn must consult with Rome.

Dr McCarthy said the Pope only wanted priests ordained before Vatican II to celebrate Latin mass because those ordained since were not trained in it.

AP: Gregorio Borgia

)Latin lovers ‘hurt, pushed to the fringes’

Father Andrew Benton, the parish priest at St Michael’s at Belfield in Sydney’s south-west, wrote that the Pope’s instruction had caused him shock, hurt and bewilderment.

“This papal document has left so many people who love the traditional Latin mass feeling ostracised, hurt, pushed to the fringes and feeling almost punished for their rightful love for this ancient liturgy,” Father Benton said in a social media post.

Melbourne Archbishop Peter Comensoli wrote to the priests of his archdiocese telling them he had, “for the time being” granted priests the ability to celebrate the traditional Latin mass privately, without a congregation present, and that it would continue in the personal parish of St John Henry Newman.

He also said the Pope no longer allowed traditional Latin mass in “parochial settings” or ordinary parish churches.

“While I acknowledge the great majority of our clergy and people will not be overly impacted by Pope Francis’ decisions, this is nonetheless a moment where the spiritual longings of some will be challenged by this call of the church to a unity in our corporate manner of praying and worshipping,” he wrote.

Facebook: Latin Mass Society of Australia

)Sydney Archbishop Anthony Fisher said he would allow the Latin mass to continue in Sydney — including at St Michael’s parish — while he takes advice on the Pope’s instruction.

In a letter to clergy, he said he was granting permission “to those priests competent in offering mass according to the 1962 Roman missal to continue to do so, either privately or in those places that already have an extraordinary form mass on their schedule”.

ABC News

)The Sydney archdiocese would not comment on whether it supported the Guild of the Holy Wounds, which says it is “attempting to establish a Sydney Oratory, which will focus on renewing Catholic spirituality through authentic liturgy”.

Hobart Archbishop Julian Porteous, in a letter to Tasmania’s faithful, wrote that:

“For pastoral reasons the existing arrangements for the celebration of the holy mass according to the 1962 missal will remain in place at this time.”

The bishops of Canberra-Goulburn, Wagga Wagga, Wilcannia-Forbes and Sandhurst have also allowed current Latin mass arrangements to continue for now.

“As an initial pastoral response, as archbishop I am very pleased with the presence of the Latin mass community in the archdiocese,” Canberra-Goulburn Archbishop Christopher Prowse said.

Not just about language

Dr McCarthy said for devotees, the Latin mass was symbolic of the pre-Vatican II church.

“They’re a particularly conservative group of people who hanker for what was before,” she said.

“In the 1950s, the church in Australia and America flourished … there was real security around everything that was being done, there was very strong hierarchy.

The status of priests, also referred to as clericalism, has been described as a “cancer” by Pope Francis.

It was referred to by the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse as something that contributed to sexual abuse in religious institutions and to cover-ups of abuse.

Getty Images: DEA / M. CAFFO

)Posted , updated