It’s been a year since I walked out of hospital, baby freshly bathed and neatly strapped into his car seat, ready to embark on the new and exciting world of parenthood.

Feeling tired but excited, we drove home to start our new normal of endless feeds, sleepless nights and takeaway dinners on the couch in our little bubble. But things quickly started to change.

On my first day of parental leave on February 1, South Australia confirmed its first two cases of coronavirus — a couple in their 60s, who were visiting from Wuhan.

But SA was a world away from the epicentre of the disease, and it felt as though authorities had a handle on it.

By the time we left hospital with our little one a few weeks later, that had all changed.

And new research has found that we were not alone.

ABC News: Michael Clements

)The world seemed to crash around us overnight

The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared coronavirus a pandemic, panic buying of essential items began and, for the first time in our lives, we considered whether we would have enough food and nappies to sustain our family for the next month.

Our GP advised us to keep our newborn away from others while the medical world tried to figure out the impact of the virus on babies.

All of the help and support we had rallied during our pregnancy disappeared overnight.

No drop-off meals, no catch-ups with friends to give a sanity check, no walks to our local cafe for a breath of fresh air and hit of caffeine after a sleepless night.

The services promised on my discharge were suspended. No drop-in clinics to check how baby and mum were doing.

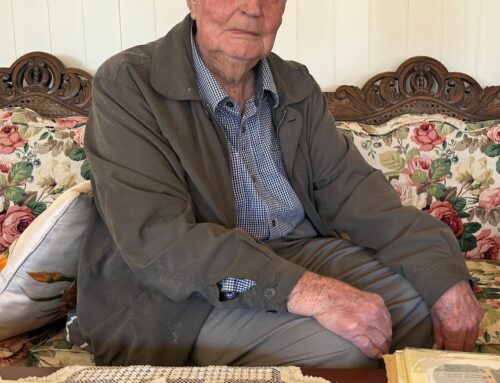

Supplied

)Without any social support — other than my very understanding husband — anxious, dread-filled thoughts began to creep in.

As the world experienced collective anxiety, ours was amplified by the fact that no-one could give us a straight answer on how best to protect our tiny newborn.

I feared letting my husband run on the esplanade with the pram in case someone with COVID-19 was running nearby.

I started mopping the floors and wiping door handles religiously, even if we had barely left the house that day.

While I now see those responses for what they were, at the time they were the only way I could get a grip on what was happening in the big, bad world.

The impact was felt by those still expecting

For those who were still pregnant, the isolation was also very real.

Many public and private services went online or stopped completely.

For my sister, who was due to give birth in May, it meant birthing classes went online or were cancelled, and her partner could no longer attend scans or appointments.

When she gave birth in the same hospital my mother works at, just metres away from her office, she only had one support person through a long and difficult birth.

When a code blue alarm sounded out through the hospital when my nephew had breathing difficulties, my mum was left just metres away, wondering whether her daughter or grandson were OK.

While in the end, my sister and nephew were happy and healthy, the experience of her childbirth wasn’t what she had hoped for.

Since then, I’ve heard harrowing stories of women being left alone to deal with devastating news while getting a scan, with no support person to hold their hand.

I’ve met mothers whose babies have needed urgent medical care, and faced endless hours in special care units isolated from family and friends.

I know women who were petrified that having their baby in a hospital setting would increase the chances of contracting COVID-19 — a fear which, for a time, drove some to have their babies at home.

And then there were the women who, wanting nothing more than to welcome a baby into the world, had their dreams put on hold when IVF and other fertility services were halted to prepare for the anticipated influx of coronavirus cases in hospitals.

A recent study from Curtin University found more than 86 per cent of pregnant women were anxious about the impact of COVID-19 on their baby in utero.

The same study found 70 per cent felt social distancing measures during the pandemic left them feeling isolated from support networks.

ABC Perth: Jon Sambell

)For those women who participated in the study, the words “isolated”, “lonely”, “anxious”, “uncertain” and “stressful” were among the most commonly used.

Lead researcher Zoe Bradfield told the ABC almost 70 per cent of mothers surveyed received no antenatal education.

“Where women couldn’t have their support people with them, where they had separation from their families when they went home, they couldn’t celebrate and join in the joyous period that usually [accompanies] introducing a new baby to your community,” Dr Bradfield said.

Things improved as the year went on

At the time my mum, who was locked away from us behind a hard border in Tasmania, told me not to let the pandemic rob me of the joy of my new baby.

I tried to focus on that comment each day and, as the year progressed, things did get better.

I still remember the first time we took our little one out to the beach for a walk one evening — when he was about two months old — and feeling like it was the first time I could enjoy being out in the fresh air with him.

Supplied

)I managed to meet a group of lovely new mums on a Zoom mothers’ group run by my local health service.

We arranged socially-distanced catch-ups, and those meetings ended up becoming my lifeline.

What makes me sad, however, is to think of the women who didn’t get the chance to connect.

Those who missed out on the baby yoga classes, coffee catch-ups and much-needed support from grandparents and family.

As a nurse who helped my son with some ongoing sleep issues recently said to me, “Last year women lost their village”.

We lost support from loved ones locked behind state and international borders, the chance to meet other expectant parents at birthing classes or in mothers’ groups during those first few hectic months.

Some of us lost access to basic services, which has left ongoing feeding and settling issues unresolved.

Some lost the chance to give birth in the way they hoped, or without the support they so desperately needed.

And while many of us won’t soon forget the impact of having a “COVID baby”, I hope the village — even partially — has returned for new parents in 2021.