They are often considered a luxury, but access to allied health services for older Australians can mean the difference between ageing well at home, being institutionalised or worse.

Key points:

- Marji Durward, almost 92, is able to access allied health services because she is entitled to as a veteran

- The royal commission into aged care said allied health had not been prioritised

- It said allied health could help older Australians live at home for longer and improve the health of those in aged care

Allied health services, which include specialist therapies like physiotherapy, podiatry, psychology and occupational therapy, were found to be severely lacking in aged care by the recent royal commission into the system.

It made recommendations to change that and put the focus on preventing illness where possible to keep people in their homes for longer.

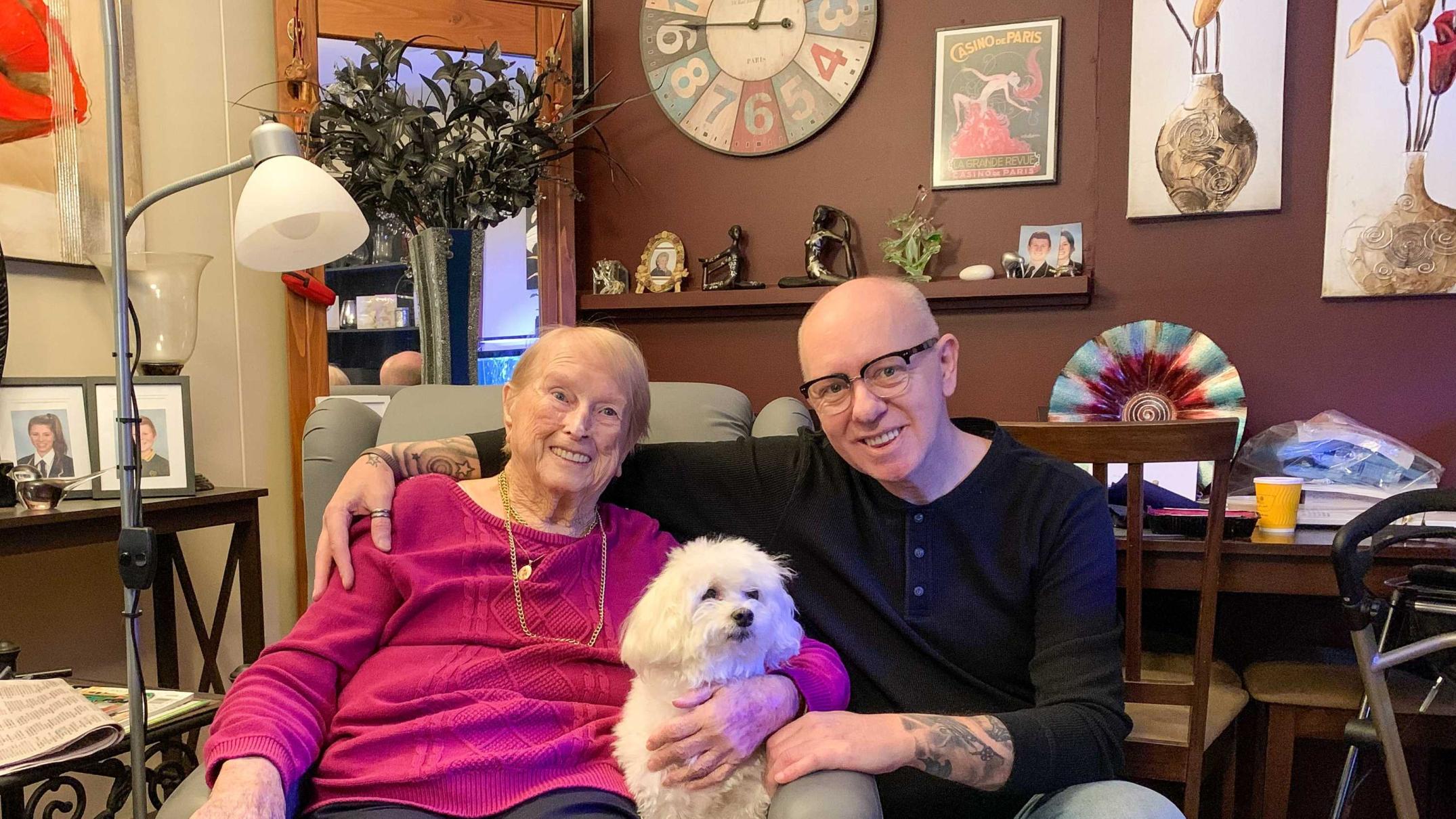

Marji Durward, who is almost 92, lives at home in Adelaide’s inner north-east with her Maltese-poodle cross Tilly and her son.

Without a band of allied health services she expects she would not still be here.

“I’d probably be up there or down there,” she said, indicating to the sky and the ground.

“I don’t know what I’d be without any of them.”

Ms Durward has Parkinson’s Disease and a range of other health concerns, she has also survived cancer and two strokes.

Her son Jeff Durward has been her full-time carer for 13 years and is quick to point out how fortunate she is, as a war widow, to have a gold card from the Department of Veterans Affairs, which gives her access to health services.

It covers treatment for all her medical conditions, including access to a physiotherapist and an occupational therapist who works with her on preventing pressure sores and providing equipment like a suitable mattress, electric bed and recliner chair.

“Unfortunately, people who don’t have a gold card fall into a category of, ‘Well, this is how much you get a year and this is what you can have’, and it’s really not enough for an elderly person to function properly in their own homes,” he said.

‘You don’t see preventative care’

Tracie McInness, managing director of Living to the Max occupational therapy services in Adelaide, said there was work to be done to ensure people receive the funding they need through in-home care packages, that the funding is transparently used and providers are accountable to their clients.

“We just see it all the time, if you don’t have access to other health services through other means and you’re purely reliant on the health care system, you don’t get any services.”

“You might get some support for shopping, cleaning and some care, but preventative services just don’t get funded,” she said.

Supplied: Rosie O’Beirne

)

Instead, she said, allied health care like occupational therapy, physiotherapy and the like are the “icing on the cake”.

“We see people under a higher package, they [people without higher-tier care packages] are not getting preventative services and if they do, it’s seen as a luxury.

“If you don’t have access, you have to follow a pathway that’s provided, rather than looking at preventative [care] — it’s more reactive.”

Royal commission found allied health had not been prioritised

The royal commission into aged care found providers had not prioritised allied health care services and that there was limited access to them for people in the system.

The final report recommended that residential aged care include allied health services, funded and matched to the needs of each resident.

“People receiving aged care do not get access to services they need to maintain their function and health,” it said.

“They should have access to a wide range of allied health services to maintain or improve their capacities and prevent deterioration as far as practicable.”

It also said assessments for care at home should identify and fund any allied care needed to restore a person’s physical and mental health to the highest level possible, to maximise their independence and autonomy.

Denying access is ageism, professor says

Denying access to preventative health services is ageism and contributes to premature institutionalisation and ill health, according to Professor Gregory Kolt from the Australian Council of Deans of Health Sciences

“It’s really discrimination on the basis of age, particularly where it relates to health care around the ageing process, what’s appropriate for people as they age and what services may or may not be appropriate from a healthcare perspective,” he said.

He argued there should not be caps on numbers, or barriers to accessing, a diverse range of services that older people desperately need.

“The longer we can keep people in their more usual and comfortable home environment for a whole range of areas for the ageing process, if we can concurrently support those people in that home-based environment I think we will see a reduction in emergency room admissions as well.”

Ageism is a theme that came through repeatedly during the aged care royal commission, on society’s attitudes and assumptions about older people and in effect how we treat people as they age.

In its final report, the royal commission noted “Commissioner Briggs considers that ageism is a systemic problem in the Australian community that must be addressed”.