It takes a moment for your eyes to adjust as you take your first steps into Archie Moore’s world.

Unlike the bustling parklands outside, a reverent stillness hangs in the air of the dimly lit pavilion.

Slowly, kith and kin reveals itself.

First, the eye is drawn to the white glow of more than 500 documents that seem to hover above a black reflective pool in the centre of the room.

Then the smaller details come into focus. Blackboard paint covers the walls, rendering the usually white cube black like the deep time of space, creating an effect not unlike the night sky.

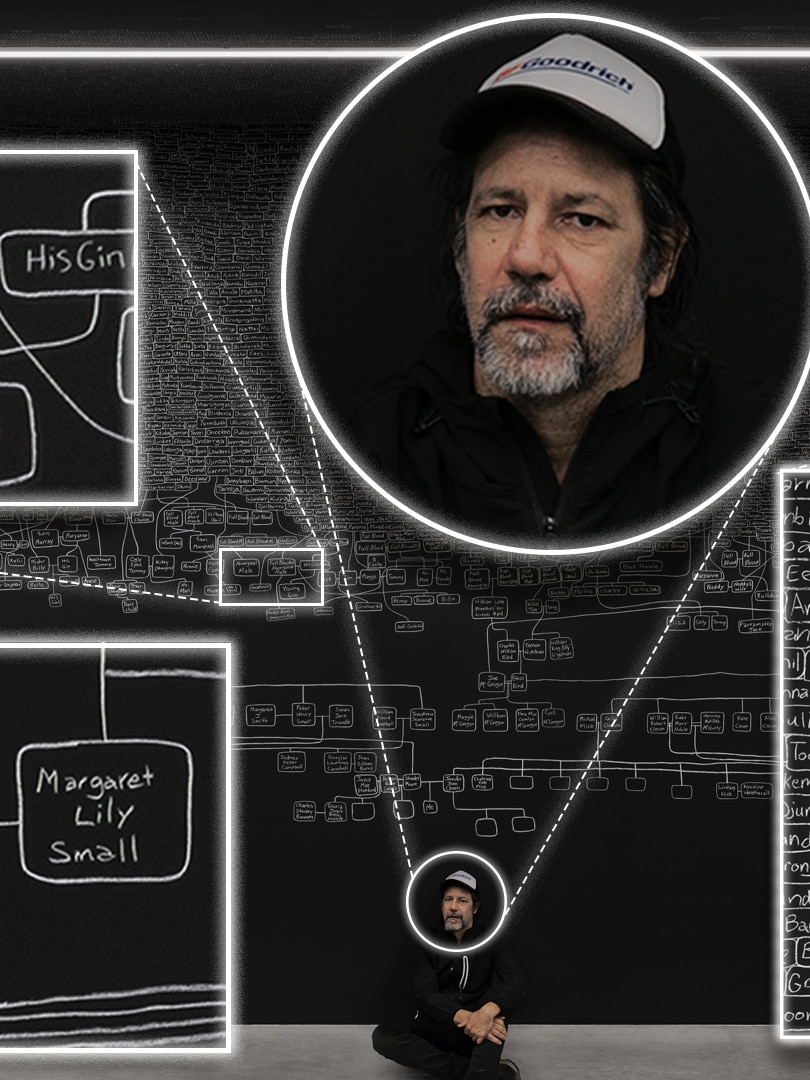

Instead of stars, Moore has hand-chalked a family tree with thousands of names of his real and speculative ancestors, branching all the way up to the ceiling.

But this isn’t just an exercise in genealogy – it’s a memorial.

And a statement on our past.

Archie Moore’s installation at the 60th Venice Biennale, kith and kin, fills all four walls and the ceiling of the Australian pavilion with a family tree.

The work’s title means “friends and family” but the old English definition of ‘kith’ broadens out to include “countrymen” and “one’s native land”.

It’s mammoth in scale — and in what it has to say.

The vast yet intricate piece won the festival’s Golden Lion, making its mark as a world-beating achievement.

But for the artist, it all starts at home.

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this article contains the names of people who have died. This story also contains racial slurs that some readers may find distressing.

Growing up, Moore knew very little about his family history.

“Both my parents didn’t speak about their families much,” says the Brisbane-based artist.

And when he was younger, Moore didn’t ask his parents very much either.

“There was a shame and embarrassment in being known as Aboriginal.”

That all started to change when his mother Jennifer Joan Cleven had a stroke eight years ago.

While she had once withheld family secrets, Moore’s mum became more talkative. And Moore became more receptive, realising the stories that would be lost if his mum died.

And so, Moore has spent the past six years building thousands of connections on ancestry websites, scouring state archives for historical newspapers and pastoral diaries, and travelling the country to speak to long-lost relatives.

Moore’s mother’s family come from the Kamilaroi and Bigambul people of what is now southern Queensland and northern New South Wales…

… while his father Stanley Moore‘s side came to Australia as English and Scottish convicts.

As Moore looked into his father’s family history, he wondered exactly what he might uncover.

“I was kind of anxious [that I] might find out some of my white relatives killed my Black relatives, or been involved in something like a massacre,” Moore says.

Something he did learn was that in 1900 his grandfather William Henry Moore was the “lucky winner” of a land ballot near the town of Coolatai in NSW.

That portion of land was at the eastern boundary of the nation of the Kamilaroi people.

… who are connected to the artist’s great-grandmother Jane Newman Boland.

“It was interesting seeing my father’s father just win this huge amount of land … and my Black grandparents living in a corrugated iron hut with dirt floor in this town, on land that their grandparents used to own,” Moore says.

His personal story of land stolen from one ancestor and “gifted” to another echoes the broader narrative of Australia’s national history.

It distils the lie of Terra nullius to its simplest form.

“In a lot of my work, personal histories seem to mirror national histories,” Moore notes.

Moore’s family tree is somewhat limited by what he can find in the historical record.

He has managed to track down photos of his maternal great-great-grandmother Queen Susan of Welltown, who worked on a sheep property on Bigambul Country in the 1800s.

But his great-great-great grandfather, recorded as Whalan Johnny, is the furthest Moore can map his direct ancestors on this side of his family.

“The little information about him marks where written records and documentation of my Aboriginal family began.”

Beyond here, the violence of colonisation becomes even more explicit.

Mimicking the offensive language used in the historical record, Moore begins to label his ancestors using only dehumanising terms like Full Blood Male, Full Blood and Full Blood Native…

… alongside Half Caste Female, H.C., Quadroon, and more.

Moore refuses to shy away from this and other derogatory language that has been used to describe his kin.

In popular usage, terms such as Gin (from the Darug “djinn” for woman) became derogatory…

… as were Lubra and Pickaninny, all used to dehumanise and anonymise Aboriginal people, women in particular.

Moore recorded these words in his work “to mark a time in Australia when these terms were more commonly used in the language of cultural conflict”.

“I found these racist words in archival documents about my family — often about members, like my grandparents, who couldn’t read or write,” he notes.

“I don’t believe the inclusion of the words in kith and kin reinstates their usage, as Indigenous Peoples refuse to occupy and entertain the terms’ denigrated meanings.”

Other ancestors were known by what were clearly mocking or joke nicknames sometimes given by station managers…

…such as Charcoal’s Kid, Greenhide Charley and Paddy Go Mad.

Some were given unlikely names – for instance Parramatta Jack, who never even visited western Sydney.

Even official records often refer to Aboriginal people by diminutive names alone. The impact is paternalistic and infantilising — Neddy, Mollie, Charley, Willie.

In contrast, Moore begins to denote his speculative ancestors using traditional names, a “reparative gesture” that bestows them dignity, previously stripped.

These names are singular and drawn from the historical record, including those who lived and worked in the same area as Queen Susan.

Moore’s art wants us to know their names, demands we say them.

Tjarki

Kidji

Teemeemaa

Jundjo

Didapool

Ngunnawonnapardi

Yembbin

Tuppilka

Munda

The linear lines of an anthropological structure melt away, leaving a density of names that rub up against one another.

“It resembles more of a First Nations notion of kinship and time, where the present, past and future share the same space in the here and now,” Moore explains.

Slowly the tree disappears, and instead what you see is a tessellation of names, rising like clouds to the ceiling.

But this seemingly seamless grid of names is not without disruption.

Fissures or black holes represent the way Moore’s family history has been disrupted by massacres, viral epidemics, and gaps in the archives.

But the web of family, of culture, weaves its way around the fissure.

Disrupted but continuous.

Alive.

The kin who were once foreign have become known to Moore, and now he’s surrounded by them.

Only a handful of people are able to view kith and kin at any given moment. On entry, staff advise you to experience and respect the artwork like you would a memorial.

As with all of Moore’s previous artworks, the big picture creates an impression while the meticulous details stay with you long after.

The sheer number of names reaching up the walls and onto the ceiling cause you to move your body in response — stretching and bending backwards in an effort to see them.

As you turn your attention to the left wall, you’re greeted by a large, low window.

It’s usually sealed in for exhibitions in this room but Moore chose to leave the bottom of it open, so passers-by can see a glimpse inside and you can see the canal that’s outside.

“The canal connects to the Venice Lagoon, which connects to the Adriatic Sea, and then to the rest of the world, and it surrounds Australia.

“So, it’s a way of showing we’re all connected.”

By leaving only the bottom section of the window exposed, the light from outside is compressed and squeezed, adding to the sombre tone of the work.

Two sets of artificial lights frame the ceiling, casting down a celestial glow.

A single bench allows you to gaze up and take in the expanse, as his ancestors did.

“I wanted the ceiling to appear as if you’re looking up into the night sky,” says Moore.

“[Kith and kin] fades into the ceiling so you’re enveloped in the tree,” he says.

“And as you look up to the ceiling, it’s as if you’re looking to the ancestors where Kamilaroi people believe we went when someone passed away – they’d go to the stars, or the dark clouds between the stars.”

The result is that the thousands of ‘kin’ present on the tree – including Moore’s mother who passed away last year – continue in our consciousness.

Lower your gaze, and amongst the ancestral galaxy on this wall, Moore has gathered Kamilaroi kinship terms, bringing his family’s language to life…

Bubbaa-tti — my father

Nganbaa-tni — my mother

Galamaay-dji — my younger brother

Bagaan-di — my younger sister

Thaya-thi — my elder brother

Buwo-thi — my elder sister

Ellie Buttrose is the curator of Moore’s kith and kin and has worked closely with him over the past year to bring it to life, giving her unique insight into the work.

“While the work in the pavilion is Archie’s family it also includes and importantly speaks to the way that First Nations people consider the landscape, the waterways, the trees and all the animals as part of their kinship system as well,” Buttrose says.

“Archie’s talking about his own family that’s very much entwined with the history of Australia that goes back 65,000 years, but he’s also saying that everyone in the world is kin.”

When Moore was at school, he was taught that Australian history started with the British arrival.

Buttrose says that with kith and kin, the artist hints at “the breadth of Indigenous knowledge that he was deprived” and that First Nations history is everyone’s history.

It’s a message that becomes evident as your eye is drawn now to the details of the room’s right-hand wall.

“This artwork is a way to just take one single thread of First Nations history and you can see that it cannot fit onto a single school blackboard …

…it’s far more expansive…

… it creeps up the walls and over the ceiling and cannot be kind of contained by a small frame in the drawing.”

By using chalk and blackboard paint as his primary tools, Moore takes us all back to the classroom to address the gap which anthropologist WEH Stanner called “the great Australian silence” in 1968.

And reminds us we still live in a time of historical amnesia…

… and a time when First Nations people still feel the ripples of trauma, past and present.

For two months Moore – along with drawing technicians Erika Scott, Luke O’Donohoe and Sam Bloor – painstakingly mapped his family tree onto the walls of the Australia pavilion by hand.

Riding scissor lifts and craning their necks, they spent hours each day drawing.

It’s an incredible feat, particularly because using chalk also means that this huge artwork could be rubbed away at any moment, and in fact it will be in just a matter of months.

“We really need to be conscious of just how fleeting life is in kith and kin,” says Buttrose.

“Chalk is a way to talk about how fragile life is and how fragile those connections are, that at any moment they could be wiped away.”

On the large table in the middle of the pavilion sit hundreds of neatly stacked documents, redacted for privacy and positioned in sight but out of reach.

Below, a black pool of reflective water looms like an abyss. By design it keeps you at arm’s length.

That void represents “the incarceration epidemic that we’re currently dealing with right now”, says Buttrose.

The documents mostly consist of coronial reports on the deaths of 557 Aboriginal people in police and prison custody since the Royal Commission…

… as well as 19 documents relating to Moore’s own family’s encounters with pernicious policies and laws.

“The coroners’ reports are displayed in a way that shows you the volume of a problem that needs addressing,” Moore says.

“There’s also blank reams of paper for representing the gaps in the record. The reports that we know exist, but we had no access to them. They weren’t publicly available.”

In (literally) centring these documents in the room while his family tree sprawls across the walls and ceiling, Moore draws an urgent and unmistakable link between historic injustices and contemporary ones.

“If you look into the water you’ll see the tree reflected … and I’ve placed the documents [on the table] as a way of saying they’re not just statistics. They’re real people with families,” Moore says.

With its celestial map of ancestors once anonymised by Australian history and its unflinching memorial to an over-incarcerated people, kith and kin reckons with a brutal shared history and points to a collective future.

The national story writ large in white chalk on blackboard paint, it is also a deeply personal work and a self-exploration. This magnum opus doesn’t sugar-coat Australia’s history or its present but, as the judges of the Golden Lion — the festival’s top award — noted in their remarks, it also “offers a glimmer of possibility for recuperation”.

In the world that Moore has created for the Australia Pavilion, we are all kith and kin – deeply interconnected.

But for you, for us, what responsibilities come with all those connections?

Archie Moore’s kith and kin is on display at the Venice Biennale until November 24. It will be remounted at QAGOMA in Brisbane.

Credits

- Reporting: Rudi Bremer and Daniel Browning

- Additional reporting and digital production: Teresa Tan

- Editing: Matt Liddy and Cristen Tilley

- Development: Julian Fell

- Photographs: Andrea Rosetti, Luke O’Donohoe, Courtesy of Creative Australia

- Video: Courtesy of Creative Australia