Tom Harkin is on a mission to “reinvent” masculinity, and it starts in high school classrooms.

As he runs workshops for teenage boys with his organisation Tomorrow Man, he finds they open up to him about their dreams for their lives — and their fears.

“The stereotype is still there that guys want to get all the girls and they want to dominate the sporting field … they want to be a dominant person,” he says.

“But that’s not everyone in the room.

“I think a lot of guys are a bit lost at the moment. A lot of young guys say it’s not a great time to be a bloke.”

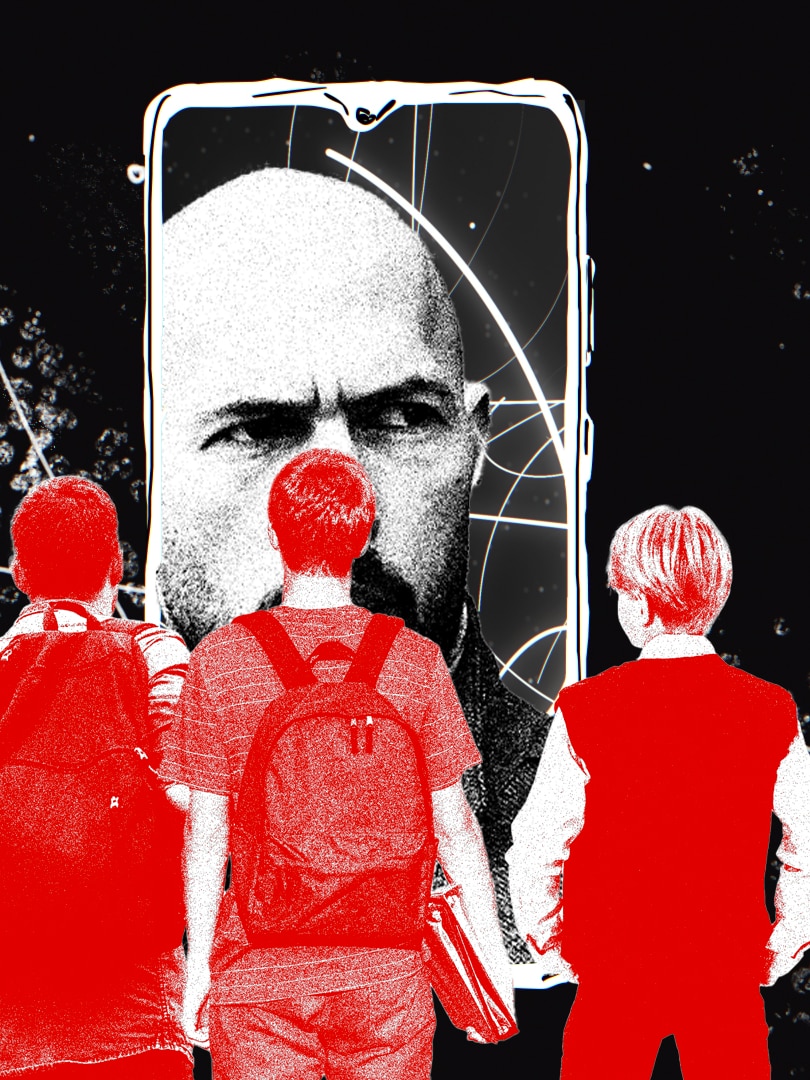

Pushing an extreme version of this stereotype are hyper-masculine social media accounts operating in the “manosphere”, an online network of groups dedicated to men’s issues that have become dominated by misogynistic, anti-feminist views.

Researchers say this content promotes violence against women, and that social media algorithms are playing a big role in amplifying and spreading it.

Mr Harkin believes its messages are also robbing boys and men of connected, fulfilling lives.

“We know that loneliness is rampant amongst men,” he says.

“We know that if you hold to rigid stereotypes you’re more likely to be involved in violent sexual encounters, you’re more likely to end up with mental distress … [and] you’re unwilling to ask for help.

“The rigid stereotype doesn’t offer you quality or depth in your relationships.”

Content encourages misogyny

Self-described misogynist Andrew Tate has become the face of this type of content, but there are multitudes of accounts pushing similar ideals.

Monash University researcher Stephanie Wescott says these accounts use “controversial and provocative” statements to attract views, and generate “millions and millions of dollars” in revenue.

Aspects of the content encourage going to the gym and building financial wealth, which many people would consider positive pursuits.

But Dr Wescott says the overall message is incredibly damaging.

“What we’re seeing in our research is that it’s changing how they [teenage boys] view girls and women in their lives,” she says.

“It’s framing women and girls in a way that they exist to be of service to men and boys, that they shouldn’t have any agency of their own, that they are inherently inferior to men.

“Patriarchy harms boys too. That’s what’s missing from these narratives.

“There’s a correlation between messages of these extreme and narrow versions of masculinity and real harm … to their mental health, to their physical health, and poor outcomes later in life.”

Fighting the algorithm

Dr Wescott says social media algorithms are pushing the content to boys “whether they look for it or not”.

“The more you view it, of course, it just becomes the only content that you see,” she says.

“[The concepts] might speak to some existing fears they have about their position in the world.

“Having those things confirmed by someone talking to you online is very powerful.”

As part of a host of changes announced last week to address domestic violence, the federal government has committed to funding a new Stop it at the Start campaign to counter the influence of misogynistic content online.

Dr Wescott isn’t convinced it will be enough, and believes the school curriculum needs a greater focus on teaching media literacy so teens can assess the content with a critical eye.

“If you want to find this content, because it’s speaking to you in a particular way, you can easily find it,” she says.

A growing counter-movement

Tomorrow Man’s workshops aim to challenge stereotypes of masculinity and help participants express emotions in a healthy way.

Queensland University of Technology professor Michael Flood says there has been a proliferation of similar initiatives in Australia in the past decade, along with an increase in government funding and policy support.

But he says they tend to be “small and scattered” around the country, and educational programs are not necessarily effective at stopping violence against women.

“There’s a solid body of evidence to show that they can shift the attitudes related to the perpetration of sexual and domestic violence,” he says.

“There’s weaker evidence that they can lower rates of actual perpetration.

“We need other strategies as well to address the social and cultural drivers of domestic and sexual violence.”

In the meantime, Tom Harkin is persevering with changing attitudes, one class at a time, and giving boys a “healthier” model of masculinity to aspire to.

“You can be strong, you can be stoic … but you don’t need to have power over people, you can have power with people,” he says.

“I think that paradigm shift is really important right now.

“We need to be as good at marketing it as [Andrew] Tate is.”

And teenage students like Jack, 17, from Adelaide, are seeing through the messages from the manosphere.

“I think it’s very hateful. It’s a horrible way to set people up,” he says.

“Young men don’t see [the misogyny] — they’re just blinded by the glamour of that life.”