John Seindanis spoke no English and only had the clothes on his back the day he took a risk that would change not only the course of his own life but the next two generations of his family’s.

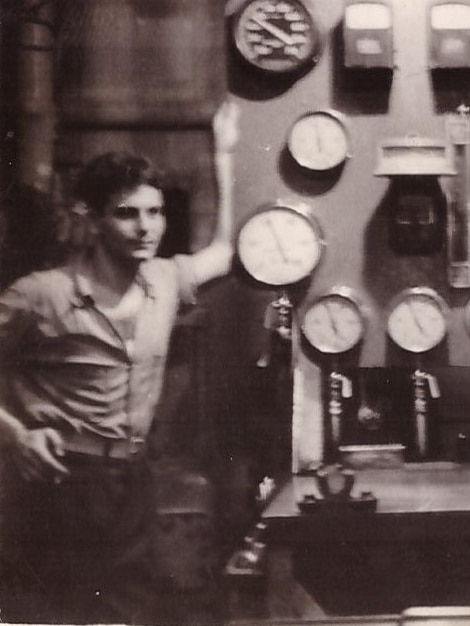

Mr Seindanis was about 22 years old and working as a merchant seaman on the cargo steamer The Pioneer when it docked in South Australia’s Port Pirie in 1954.

As the steamer pulled in to collect a shipment of lead concentrate bound for England, Mr Seindanis and six other Greek men made a run for it.

The seven deserters spent 22 days hiding from the ship’s captain and authorities in the Flinders Ranges.

According to Mr Seindanis’s son, Nick, the men’s brazen bid to start a new life in Australia was made possible through the kindness of local man Bill Frangos.

For nearly a month, the farmer, who came from Ikaria, the same Greek island as Mr Seindanis, kept the seven “ship jumpers” hidden on his property in the neighbouring town of Nelshaby, where he offered them food, shelter, and safety.

“If you got caught before the ship left the harbour, you’re in handcuffs back on the ship,” Nick Seindanis said.

“There were the remnants of the Morgan-Whyalla pipeline … and they sat in those pipes on rocks.”

After The Pioneer left the port, the group emerged from hiding and turned themselves in at the police station.

They paid a 10-pound fine and were subjected to a good behaviour bond before later being naturalised.

‘Jumping ship’ during the post-war years

Stories of “jumping ship” were common among Greek migrants in the years following World War II and the Greek Civil War, which raged from 1946 to 1949.

Crippled by economic distress, there were few jobs in Greece so many of those seeking new lives set their sights on Australia and America.

But migration was not an easy process, and people like John Seindanis did not have the necessary papers to come to Australia, his son explained.

“There were no factories on [the] islands, so there was no work,” Mr Seindanis said.

“Most of them got jobs as merchant seamen … He’d been on [The Pioneer] for three or four years, and they’d inherited a really tough captain … [who] even withheld money from them.”

As fate would have it, the farmer who helped the seven men escape introduced John Seindanis to his sister and the pair fell in love and got married.

The migrant story of the Seindanis family is one of the many Nick Seindanis has written about in his recently published book to mark a century of Port Pirie’s Greek community.

A good place to flee to

Established in 1924, the Greek Community of Port Pirie is the oldest Greek club in South Australia and the second oldest in the country.

By the time Nick Seindanis’s father arrived in 1954, the Spencer Gulf town already had a thriving Greek community as Australia experienced its second wave of post-war immigration.

However, according to Mr Seindanis’s research for his book, History of Greeks in Port Pirie: Celebrating 100 Plus Years, the first Greek person moved from Crete to the town in 1861.

Miltiadis Dimitrios Bidzanis had to flee his homeland “real quick” after he was involved in the murder of an Ottoman Turk, so he became a merchant seaman.

“When he was naturalised, they [the authorities] asked him if he wanted to anglicise his name,” Mr Seindanis said.

“He had a bit of a think and he said: ‘Deer’.

“He was a very fast runner as a young man in Crete, and in the village he’d earnt the name ‘elafi’ … ‘elafi’ in Greek means ‘deer’, a fast-running animal.

“His middle name was ‘Dimitrios’, [so] he wanted Miltiadis Di, so he emphasised the ‘D’, Deer.

“It started as Deer, but now it’s changed to Diar.

“The De Diars were the first Greeks in Port Pirie.”

Greeks on Florence Street

To this day, Port Pirie’s Greek club and Greek Orthodox church on Florence Street are “the epicentre” of the local Greek community.

“Next door to the Greek club was a pinball parlour, next door was a Greek continental shop, a pizza bar, a kafenio … a card playing Greek coffee place, a meeting place,” said Mr Seindanis, reflecting on the past.

“Across the road, the Siderises owned the Central Hotel, and then of course we had the Greek church.”

Club secretary and Mr Seindanis’s sister, Koula Korniotakis, said the club was still thriving with members of all ages.

“We try to have a lot of multicultural events and we still honour the [Greek Orthodox] holy days,” she said.

Ms Korniotakis helped research and edit the book and typeset the entire text, which she said was “very emotional” for her.

“Especially when I read the family stories,” she said.

“There were a lot of touching stories, people who fled Greece, people who got shot at, that was very emotional.”

Greeks around South Australia

Flinders University associate lecturer Yianni Cartledge — who wrote his thesis on the migration of Aegean islanders to Australia and the United Kingdom from 1815 to 1945 — helped Mr Seindanis research his book.

Mr Cartledge said Greeks settled all around regional SA, with the first Greek in the state arriving in Port Lincoln in 1842.

Georgios Tramountanas, who anglicised his name to George North, is still considered “kind of a pioneer of Greeks in SA”.

“There’s a good portion of the West Coast that had Greek links, especially if anyone had relation to the North family,” Mr Cartledge said.

Mr Cartledge coined the term “the Port Pirie system” to describe how Greeks in the town helped the newer arrivals.

“[They] knew Port Pirie as a destination, they would arrive in Port Pirie … as most did, they had an address on Florence Street where they would stay with a relative, a friend or a sponsor,” he said.

“From there, the Greek community of Port Pirie would essentially help with housing, finding work … being a safety net for those who had arrived and didn’t have exact direction of what they were doing.

“It was drawing other Greeks in, and then from there, they would get settled and then disperse to other parts of Port Pirie or other parts of SA.”

Mr Cartledge said Port Pirie had the largest Greek population in South Australia leading up to the 1920s, and it formed a “strong link” with those in Broken Hill through the towns’ respective smelters.

“A lot of the Greeks at the smelters in Port Pirie eventually found work as well in Broken Hill and there was a lot of back and forth,” Mr Cartledge said.

“Even the Greek Orthodox Church in Port Pirie was given dominion over Broken Hill as part of their congregation as well, so the priests were going back and forth.

“Really, Port Pirie and Broken Hill were the same community in the early days.”

Many Greeks in Port Pirie then made a “secondary migration” to Adelaide or Port Adelaide around the time of the Great Depression when some of the smelters shut down, increasing Adelaide’s Greek population.

“Greeks have left their mark all over South Australia,” Mr Cartledge said.

“There is a strong sense of maintaining cultural identity among Greeks, even to the fourth, fifth, or as Nick Seindanis points out in the book, sixth generation now, of some of the Greeks in South Australia.”

Ship jumpers’ amazing legacy

Mr Seindanis dedicated a chapter in his book to the seven ship jumpers and their legacies in Australia.

“I’ve tracked down all their families, most of the grandkids are doctors, lawyers, big business people,” he said.

“From the term ‘illegal immigrant’, to what these seven people have contributed to Australian society, is just amazing.”

Posted , updated